Lights out on River City? A legacy of talent and the struggle to save Scotland's soap

Three former crew members reflect on their time working on River City and the legacy the show leaves behind

In the fictional streets of Shieldinch, Scotland saw itself. For over two decades, River City was more than just a soap opera tucked away on BBC Scotland’s schedules- it was a training ground and for many, a second home.

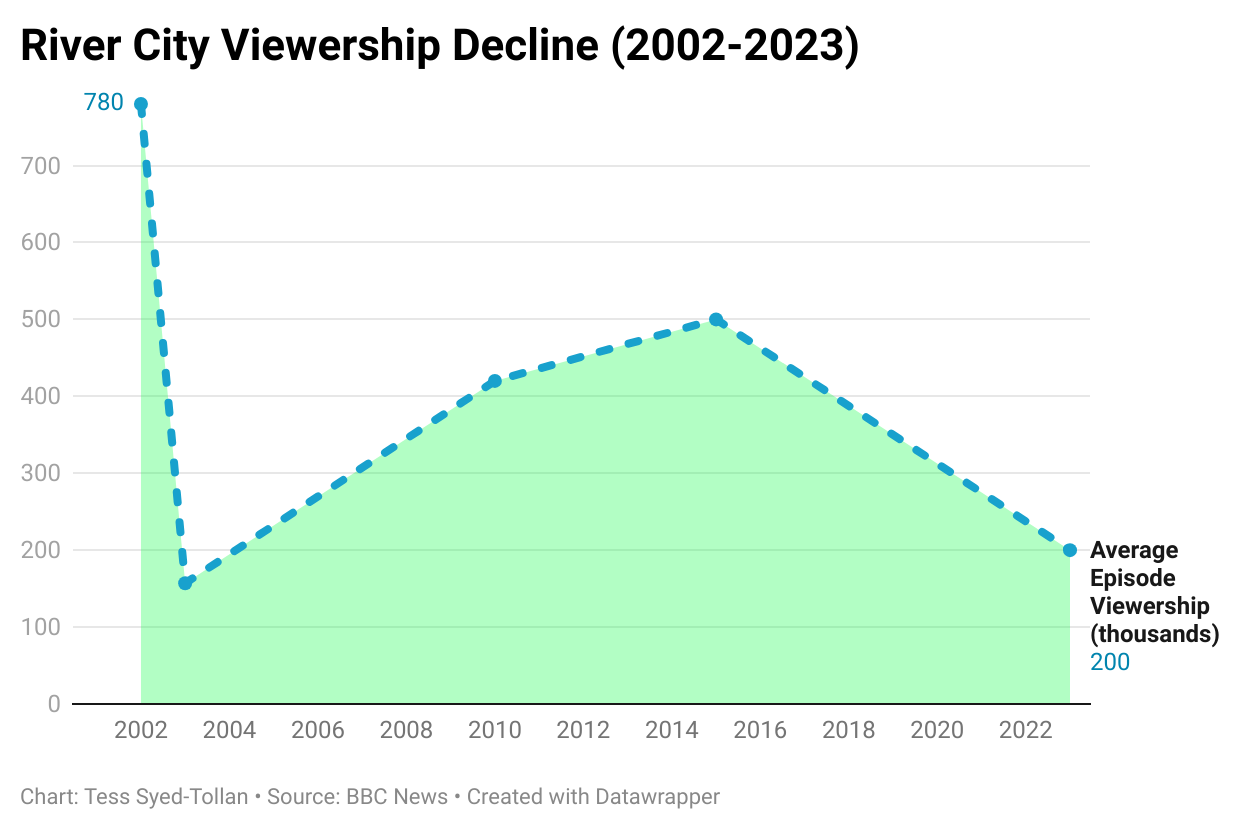

Now, as the BBC moves toward winding down production later this year, citing changing “viewing patterns”, those who carved out careers for themselves on Montego Street are speaking out. They’re grieving not just for a TV show, but for a cornerstone of Scotland’s creative industry and the family it built.

As stars of the show took to the streets of Edinburgh this week to protest its cancellation outside Holyrood, I spoke to three former crew members to reflect on how River City shaped their careers and what legacy the show is leaving behind for Scotland’s television industry.

“It sort of speaks for itself when you look at who’s come through it”

You could say River City is a family affair for Mark Gordon, who worked as a third assistant director (3rd AD) on the show from 2018 to 2021.

“We’ve all worked there”, he tells me proudly.

“All of my immediate living family, my dad, my brother and my wife, we’ve all worked there”

“My brother was one of the Brodie’s, he’s in it just now”.

Gordon’s own route onto set came after a chance email to the production manager. He’d been working his first television job as a runner and driver on BBC One Scotland’s “Scot Squad” and was encouraged by fellow crew members to try his luck at River City.

He recalls humorously, “It was as simple as I sent the email, a few people vouched for me, I went down and met Andy (production manager) and he showed me around and offered me the job”.

While initially starting as a runner and driver on set, he eventually progressed to 3rd AD, crediting that initial foot in the door as his introduction to the industry.

Gordon’s affection for River City is undeniable. Even when I ask him about the legacy of the show, he is quick to remind me that there is still a campaign to save it, perhaps hinting that the word “legacy” could be a hasty one.

Despite this, he speaks passionately about the “incredible talent” that has passed through Dumbarton Studios, the purpose built facility that was an integral part of “drama factory” envisioned by the show’s creator, Stephen Greenhorn.

“There’s some incredible logistical minds and like, crew that have come through there as well. From the ground up as well”, he tells me.

“There’s a gentleman who started as a camera trainee at River City and is now a director at River City. He went through the whole camera department and moved over to directing and he’s been very successful”.

“It sort of speaks for itself when you look at who’s come through it”.

From its inception, River City was destined to become a training ground for emerging film and television talent in Scotland.

Fergus Mitchell was one of the early writers on the show, joining the production at a time when it was still finding its feet and its voice.

Over a crackling phone line which periodically cuts out, he tells me, “I was in the kind of original intake of new writers, which was part of the remit of the show to create a factory for talent in Scotland, so I felt very much part of that and it felt very kind of empowering”.

Mitchell describes his path into the industry as “torturous”, having studied audio-visual media at college, before volunteering at the National Film and Television School in London and gradually building up contacts.

When he was eventually approached to write on the show at the end of 2002, he remembers, “It was quite awe inspiring as a new writer to realise that I had this as a kind of playground, if you like”.

River City helped him refine his skills as a writer and offered him the stability that the industry often lacked.

He doesn’t shy away from sharing the brutal reality of the job, which he describes as “non-stop”, yet it was the unrelenting nature of the work where he really found his rhythm and honed his craft.

“If you’ve only got say, 10 days to do it, then you have to kind of sort yourself out and become more practised”.

“You are part of a process and it won’t wait for you”.

He also stresses that the stability the show offered was unique in an industry that could be “ kind of lonely” and “unstable”.

“I think the fact that there was something that gave stability to a lot of people was really important”.

“If you’re worried about where your next job is coming from all the time, you’re not doing your best work”.

It’s clear from speaking to him that his time on River City is a period remembered with great fondness and gratitude, not only for the opportunities it afforded him but also the “great folk” he met while doing it.

Yet he seems less optimistic about salvaging the show than Gordon.

“The idea that River City can survive in its current format is extremely unlikely” he admits.

When I bring up the ongoing campaign to save the show, including the over 10,000 signature strong petition launched by Equity; the trade union for the performing arts and entertainment industries in Scotland, he seems resigned in his outlook.

“I don’t think it’s going to make any difference to the BBC, because they think long and hard about their decisions”.

Yet, for Joshua Haynes, who worked in the AD department on the show for a number of years, those 10,000 signatures are “symbolic” of how important the show is to people in Scotland.

“It’s a show with Scottish speaking people about Scottish stories and that just doesn’t happen a lot”, he suggests.

While admitting there may be a touch of melodrama sprinkled throughout life in Shieldinch, such as “criminals and gangs and murders, things getting blown up”, Haynes is confident that River City is a “very good reflection” of what life in Scotland is like and for that reason, it resonates with its audience.

Haynes describes himself first and foremost, as a professional actor, who, prior to working on River City had numerous TV credits, including “Mack” in the CBeebies series “Molly and Mack”.

Keen to build his repertoire and stay working within the industry after his five year stint on the show, he eventually found himself joining the AD department on River City for a couple of years.

It was here that he gained his first experience of directing.

“I went on to shadow a director for a couple of months and managed to learn quite a few tricks about directing and how it works and how you would shoot something on something like a soap, which is multi-camera, very fast-paced environment”.

The best part?

“At the end of those two months I ended up directing a scene for River City”, he gushes excitedly, describing it as one of the proudest moments of his life. I can almost hear him beaming over the phone.

His energy is infectious and it’s hard not to share his enthusiasm for the show during our conversation.

He adds fondly, “Every single one of the crew was incredibly helpful and cooperated with me brilliantly”.

“There was a real kind of, familial love in that place”

“It’s a family, it really is a family”.

Family. This word keeps popping up, not only in my conversation with Haynes, but also with Gordon and Mitchell. In an industry that, like Mitchell mentioned, can often feel lonely - that family mattered.

Since launching in 2002, River City produced more than 1,200 episodes and helped fuel an industry now worth over £567 million a year to Scotland’s economy, according to Screen Scotland.

It gave hundreds of actors, writers and crew members their first break and often, their first steady paycheque. According to Creative Scotland, more than 10,000 jobs are supported across the country's film and television sector.

Yet without places like River City to develop homegrown talent, there is growing fear that Scotland's expanding TV industry will rely increasingly on importing experience, or worse, that young Scottish creatives will be shut out altogether.

That is why, Haynes believes, it is crucial for people to support the campaign to save River City.

He argues that regardless of whether you watch the show or not, it’s about “respecting that this is an institution that employs a lot of people in this country and represents this country in a way that isn’t getting represented anywhere else”.

Gordon shares Haynes’ sentiment. While insisting that he is not an authority on the subject, he suggests that the best outcome would be to save River City and “revamp” it somehow so that it maintains the interest the BBC says it’s losing.

“There’s still the option to not lose River City” he stresses.

Then, after a pause, he adds simply,

“It’s just a bit sad for it to be going.”

Equity’s petition to save River City can be found here: Save River City